Pollock in a Thrift Shop

California truck driver Teri Horton "devoted much of her time to bargain hunting around the Los Angeles area." In the 1990's she found a $5 painting in such a place and now, according to the NYT's Randy Kennedy:

Even the most stubborn deal scrounger probably would have been satisfied with the rate of return recently offered to her for a curiosity she snagged for $5 in a San Bernardino thrift shop in the early 1990s. A buyer, said to be from Saudi Arabia, was willing to pay $9 million for it, just under an 180 million percent increase on her original investment. Ms. Horton, a sandpaper-voiced woman with a hard-shell perm who lives in a mobile home in Costa Mesa and depends on her Social Security checks, turned him down without a second thought.The NYT goes on to describe the movie and writes that:

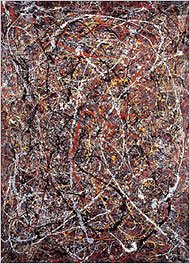

Ms. Horton’s find is not exactly the kind that gets pulled from a steamer trunk on the “Antiques Roadshow.” It is a dinner-table-size painting, crosshatched in the unmistakable drippy, streaky, swirly style that made Jackson Pollock one of the most famous artists of the last century. Ms. Horton had never heard of Pollock before buying the painting, but when an art teacher saw it and told her that it might be his work (and that it could fetch untold millions if it were), she launched herself on a single-minded post-retirement career — enlisting, along the way, a forensic expert and a once-powerful art dealer — to have her painting acknowledged as authentic by scholars and the art market.

She is still waiting, defiantly, for that recognition and the payoff it could bring. But as a kind of fringe benefit, her tenacity has made her into a minor celebrity, a pantsuited David flinging stones at the art world’s increasingly wealthy Goliaths. Now it has also landed her the starring role in a documentary scheduled to open next week in New York and later around the country, called "Who the #$&% Is Jackson Pollock?" (When Ms. Horton asked this of her art teacher friend, the original question included a word that cannot be printed in this newspaper nor, apparently, blown up on movie marquees.)

The movie, directed by Harry Moses, a veteran television documentarian, was produced by him; Don Hewitt, the creator and former executive producer of "60 Minutes"; and his son, Steven Hewitt, a former top executive at Showtime. Mr. Moses said he first became aware of Ms. Horton’s quest when he was approached by Tod Volpe, a high-flying art dealer who fell to earth, and landed himself in prison, in the late 1990s for defrauding several of his celebrity clients, including Jack Nicholson and Barbra Streisand.It gets better! "It became, really, a story about class in America," Mr. Moses said. "It’s a story of the art world looking down its collective nose at this woman with an eighth-grade education."

Mr. Volpe, who has harbored dreams of breaking into movies, proposed collaborating with Mr. Moses on a 10-hour documentary mini-series about corruption in the art world, a subject he said he knew well.

One aspect of the story that bugs me is the following:

She is arrayed against a formidable team of establishment skeptics, including Ben Heller, an early Pollock collector, and Thomas Hoving, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who examines the painting in somewhat dramatic fashion, tilting his head and almost touching his nose to the canvas before pronouncing it “dead on arrival.”And here is what bugs me:

Later in the movie Mr. Hoving says that Ms. Horton has no right to be bitter about her treatment by the art world and adds sternly, when told that she would vehemently disagree: “She knows nothing. I’m an expert. She’s not.”

Hoving, in spite of his "False Impressions" book, as far as I know, is not a Pollock-specific expert.

And that counts. Although a Rembrandt expert could probably have an educated opinion, after some real examination, if a Vermeer painting stands a chance of being a real Vermeer, only an experienced Vermeer expert, armed with some forensic tools, can make a semi-final determination about a suspected Vermeer being real real or fake.

And "experts" are wrong all the time! Remember this "fake" Vermeer?

The only thing that the best of experts can determine quickly by examining a drip painting close-up is to verify that it is indeed a drip oil painting (as opposed to a reproduction, or a flatter watercolor, etc.).

An expert with an open mind would have turned the painting around, and examined the back of the painting to see if the canvas was stretched like Pollock canvasses, if the nails or the staples used to anchor the canvas were the same that Pollock used, if the type of canvas was the same type (or brand, or weave) that was used in real Pollock paintings, if the canvas was stapled/nailed on the side or on the back (artists are creatures of habit, and Pollock probably did it the same way all through his life), if these nails or staples has the same aged appearance that a decades old painting should have, are the sides of the painting "painted" or left virgin?, is the canvas primed or raw?, etc.

In other words, no real open-minded expert just looks at a painting (which is so closely visually similar to Pollock's work - at first sight) and makes a haughty judgement like that.

And then science takes over to verify the work, looking for other scientific consistensies (or lack thereof) between this $5 Pollock and the multi-million dollar ones.

Hoving may have been a decent and flamboyant Met director, but he's dangerously approaching being labeled a hack as an "expert" if he claims to be able to determine a painting's validity with a quick glance.

Read the whole article here and then read Bailey's take on the whole subject and his offer to Ms. Horton here.

No comments:

Post a Comment