Shauna Lee Lange on Andrea Reed's Sweet Struggle at The Target Gallery

Power Seeks a Vacuum

By Shauna Lee Lange

Years ago when I was working in Newport, Rhode Island, I had a mentor with whom I could safely share some of the idiosyncrasies of working with certain personalities. And I still remember what he said.

Power seeks a vacuum.

Meaning that power goes to where there is a void, to where the void can be filled by a personality larger than itself, and to where there is no competition.

And so it is with artwork that arrests us in its riveting, shocking, and disturbing elements. Powerful artwork causes one to shift entirely. And when that powerful artwork is directed at a subject that exists in everyday life, that we all walk around living with, but no one seems to really want to squarely address, well that's power seeking a vacuum.

Andrea Reed's problem, if she has one, is that she does not yet fully recognize the potentiality for the vacuum sucking up the her work or its message. If I had her here with me at this moment, I'd be doing some serious career planning with her and not just career planning the art world.

Andrea Reed's problem, if she has one, is that she does not yet fully recognize the potentiality for the vacuum sucking up the her work or its message. If I had her here with me at this moment, I'd be doing some serious career planning with her and not just career planning the art world.

She's Al Sharpton and Jessie Jackson reincarnate. She's Rosa Parks and Harriet Tubman and Grandma Moses and Salvador Salgado, but she doesn't know it.

I wonder what's more dangerous: having the power, hitting the mark, daring to speak the communication, or doing all of that and not having any inkling of what you've accomplished.

I imagine it's kind of like sitting at a slot machine when you're an inexperienced gambler and then you hit the jackpot and you're not really sure what actually happened or what comes next. It's amazing, you're happy, you're thinking about the money; but you have no clue what it is you've actually done or how rarely it happens.

Several times during last night's opening reception at Alexandria's Target Gallery, one could hear the words, “powerful,” “disturbing,” “brave,” and “raw.” And all those adjectives are all true.

Reed seemingly does not completely recognize the timeliness of her black/racism/social condition message in a day of Duane Chapman, Don Imus, and Michael Richards and the controversies over demeaning language, its use, its application. Nor does Reed realize the power of an introspective and respectable examination of black stereotypes, black societal problems, and the black experience. She’s timely, she’s ahead of her time, and she’s behind the times all at once, it’s incongruent and it’s fascinating.

She says it herself: "I was fearful of how people would perceive the work."

And as you age, you realize that all that time you spent worrying about what other people think was time wasted. Why should she care what other people think of her blackface images? It’s honest. It’s true. It’s presented in a nonjudgmental way, almost like a mirror. I want Reed to walk proudly. What she’s done is amazingly brave. She’s worried the black population will see her as airing dirty laundry; she’s worried whites will see her as capitalizing on negative stereotypes; she’s worried about staying true to herself; and she’s swimming in a sea of contemplation. And I want her not to give a flying frog about what anyone else thinks, because when you’re a visionary, you get to stand alone.

And it’s lonely, and it’s scary, and it’s all the more powerful because you’re the only one responding to the call, listening to the drumbeat, answering the higher cause.

And as I was walking through the Target Gallery - and there's a lot of glare from the overhead lighting there - and I was thinking about how the glare in this case actually accentuates the large scale color photographs (a series of 10 diptychs on crimson/blood red background), giving a reflective appearance. It’s sort of like passing through the Vietnam Memorial; you can see yourself looking in at the picture. How powerful is that?

Today, the morning after, I find myself still conflicted about Reed. On the one hand, I feel bad that she herself honestly says, “I’m not exactly sure where I’m going to go. I don’t think the project is over and I want to continue with it.” She needs a serious mentor. She’s talent untapped. She’s it. She’s the real thing. And I’m thinking that Reed may not know where she's going to go, but I surely I have an idea.

I’m reminded of the time I saw Yoko Ono’s work in San Francisco. This is an artist! This is art!

And so it is with Reed. She has difficulty articulating what she’s trying to say, but the thing of it is - she doesn’t need to. It’s clear. It’s blackface. It’s the mask worn. It’s the clownish behavior. It’s the mask of who we are as a people and what we do. And who is behind the mask. We’re ignorant, you know, white and black, all of us – and what do we think about it? Killing each other, gang violence, fatherless homes, selling out in exchange for the big house, broken self esteem, trying to achieve unreachable ideals established by someone other than ourselves, searching through meaning in acquisition of money, and things, and respect, and acceptance. Oh Lord.

On the other hand, I’m so excited about Reed. She admits, “I’m young, I’m still growing, I’m still trying to find my voice.” One of the things about youth, and I would tell Reed this too, is that you don’t know what you had at the time you had it until much later in life. Any of us who goes back to look at a photograph of an earlier self may catch themselves saying, “Damn. I looked good.” But we didn’t really know it at the time, did we?

Reed doesn’t know what she has. She hit the jackpot, the end of the rainbow, the statement and work that takes some artists and photographers a lifetime to achieve. And she has it. She has it now. She could stop. Right here and never do another thing. She could go on tour. She could give lectures.

Commercially, she needs marketing; she needs exposure; she needs mainstream.

Personally, she needs serious representation. She needs mentors.

Reed can be the next voice of the people. Reed’s a revolutionary; she’s a seer; she understands; she gets it; she communicates it; she dares.

I go back through the gallery and I imagine the next life of these works. I’m thinking about redesigning the entire Barbie Doll Headquarters Enterprise. I’m imagining walking into a reception area with Reed’s “Barbie Girl” hanging behind a coiffed and reserved corporate greeter in front of a massively cold marble wall. “Barbie Girl” is an image that shows a young black woman, in hideous blackface makeup, squeezing the waist of a blonde, white Barbie Doll. A figure the woman will never have. A culture the woman will never relate to. And in the interim, the woman is holding her own mid-section. The smallest part of her is ever so enormous compared to the smallest part of the doll. This is what I mean by power.

Reed’s tapped into every woman’s pain. Every woman’s inability to reach Barbie Doll perfection. And it’s not enough that she points to this feminist, beauty, perfection complex, she then adds the experience of being black and being a black woman in this culture on top of it. It’s quiet, yet it yells. It’s subdued, yet it feels like being submerged.

Fear is a powerful thing. And I suspect Reed is fearful on some subconscious level of what she’s actually achieved. She has the vision of what she wants to say, yet she steps back from really standing firm in her own conviction. And this comes with age, too. She spoke last evening about how the experience of showing at the Target Gallery and the attending the exhibition was a bit overwhelming for her. She stumbles a bit as she speaks. She’s embarrassed when slide photos come up too dark on the viewing screen.

None of it matters.

You, Ms. Reed, overwhelm us! You’ve taken survey. You’ve taken a look around at the black experience. You’ve said this is what’s ugly to me and not only is it ugly to me; it should be ugly to all of us. And you’re right. Completely right.

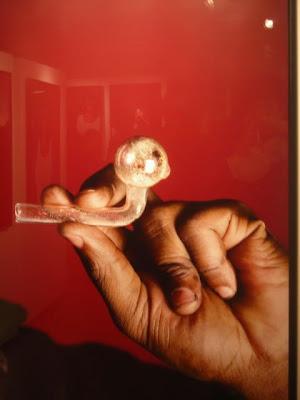

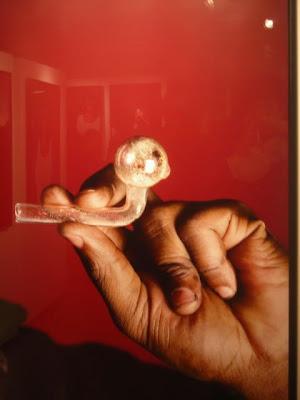

Reed speaks about using the light in the photographs in an ominous way. And she shares the story behind “Crack Head” and her attempts in San Francisco to acquire a crack pipe for the photograph. She explains she went to several places and honestly communicated what she was trying to do and her vision for the photographs and still was met with resistance, mistrust, or disbelief. She states her own personal experience was altered from this difficult project. One attendee pointed out that the hand of the young man who is holding the crack pipe is dirty and grainy. Reed states this is a result of having each of her models apply their own blackface makeup and the residue resulting from that. And she says interestingly that once the models finished with their masks, there was a distinct transformation and a very different energy in the studio, one she tried to capture on film.

I wonder whether Reed considered not using blackface, and truly I was encouraged by the amount of research and background Reed conducted in approaching the project. The images of the elements of our culture would have been just as powerful without blackface as they are with. The blackface is an added and very strong message about the ridiculousness of such a life – who are we entertaining? Where is the enjoyment? Why is no one laughing?

Reed says she felt she needed to make a statement about how blackface started in the white community and then was an “art form” adopted by black artists. She says she struggles to portray these issues and all of sudden, the lecture space becomes electrified and a little nervous when one attendee asks whether it would have been a different viewing experience if Ms. Reed were white.

What? You have to be black to portray black issues?

You can’t understand what it is for the rich when you’re poor? You can’t understand or portray nature as an artist if you live in the city? My head started spinning; Reed handles the question with grace.

She’s young. She’s introspective. She’s from small town Peoria, Illinois, and she attended Howard University, and now lives in California. Her show features a piece entitled “The Bluest Eye.” It is inspired by Toni Morrison’s novel of the same name. And as I write this, my breathing becomes a little tight, for some reason, I still want to cry. The photograph shows a young woman removing the blue contact from one of her eyes and balancing it so gingerly on the tip of her extended finger. She has a skin condition, and she’s not Halle Berry. This is realism at its best. This is current, contemporary culture. Striving to be something we’re not out of rejection of what we are.

This is all of us, balancing some aspect of ourselves, whether its work, family, health, finances, ever so lightly on the tip of a finger, able to be blown away with the slightest wind.

Fragile.

So fragile and so fruitless this constant struggling to be something else.

Of the ten works, any one of Reed’s diptychs could stand alone. Fully alone in a one-woman show. And she’s clever, that Reed. You’re so fascinated by the semi-automatic pointed to a young man’s head that you hardly even see the weapon has the same embedded line as the young man’s wife-beater t-shirt.

Power. Care. Honesty. Shock.

Reed’s saying, I see it and this is what I do about it. I make it art so others can see it too. I ask the question. And if that’s not a leader, I don’t know what one is.

She speaks about the work from a technical perspective. The feel, the focus, the framing. She shares how she worked with people she knew to create authentic characters, used Polaroids for tests, and opted for the split frame. You see, when power finds the vacuum, power wants to fill it. So Reed split the frames into large format diptychs because she wanted to show racism’s fragmentation. The separation from the whole. And the black frame is impenetrable, a border that cannot be broken.

These are the reasons Reed won her spot on the highly competitive Open Exhibition Competition. I wanted to embrace the gallery management, and believe me; I rarely feel the urge to do that!

The Target Gallery's mission is to challenge perspective, and gallery operatives stated last night’s turnout was one of the best yet. Reed’s work was selected by a blind outside juror panel. The show runs to December 2, 2007.

He also worked very hard in public art projects that brought a new refreshing look to public art: He was the winner for the International Competition to design the New Orleans AIDS Monument. Also Tate public works are at Liberty Park at Liberty Center, Arlington, VA; The Adele, Silver Spring, MD; at the US Environmental Agency, Ariel Rios Building Courtyard, Washington DC; at the National Institute of Health, Hatfield Clinic, Bethesda MD; at the Upper Marlboro Courthouse, Prince Georges County MD; at the American Physical Society, Baltimore Science Center, Baltimore MD; at The Residences at Rosedae, Bethesda MD; Holy Cross Hospital, Silver Spring MD; The Carmen Group, Washington DC and many others in process.

He also worked very hard in public art projects that brought a new refreshing look to public art: He was the winner for the International Competition to design the New Orleans AIDS Monument. Also Tate public works are at Liberty Park at Liberty Center, Arlington, VA; The Adele, Silver Spring, MD; at the US Environmental Agency, Ariel Rios Building Courtyard, Washington DC; at the National Institute of Health, Hatfield Clinic, Bethesda MD; at the Upper Marlboro Courthouse, Prince Georges County MD; at the American Physical Society, Baltimore Science Center, Baltimore MD; at The Residences at Rosedae, Bethesda MD; Holy Cross Hospital, Silver Spring MD; The Carmen Group, Washington DC and many others in process. The art fairs have also played an important part. SOFA NY was the start a couple of years ago, followed more recently by SOFA Chicago and AAF NY and also artDC. He's now heading to Art Basel Miami Beach where his work will be at FLOW. At the last fair in Chicago, Tate sold 14 sculptures (including a museum acquisition), and I am told that his newest video pieces were the buzz of the fair. In "Call for Redemption" (to the right), a motion detector triggers a video while a small speaker wails the Moslem call to prayers recorded by Tate at Istanbul earlier this year (where he was with Michael Janis teaching glass techniques at a workshop in Turkey).

The art fairs have also played an important part. SOFA NY was the start a couple of years ago, followed more recently by SOFA Chicago and AAF NY and also artDC. He's now heading to Art Basel Miami Beach where his work will be at FLOW. At the last fair in Chicago, Tate sold 14 sculptures (including a museum acquisition), and I am told that his newest video pieces were the buzz of the fair. In "Call for Redemption" (to the right), a motion detector triggers a video while a small speaker wails the Moslem call to prayers recorded by Tate at Istanbul earlier this year (where he was with Michael Janis teaching glass techniques at a workshop in Turkey).