Yep... the 1930s!

We

all owe a tremendous debt to Jackie Robinson. Not only because of Major

League baseball integration, but more importantly, because of the

significant advancement of race relations worldwide that was the real

aftermath of his actions during and after his baseball career. His

sacrifices must never be forgotten or diminished, and Robinson was and

will always be a hero, not just for Americans, but for mankind.

This story is all about the Cubans, and the American confusion between race and ethnicity and the racist notion of the "one drop rule." At the heart of the story is the fact that Caucasian Cubans who could prove pure European ancestry were allowed to play in the United States, and many American white players played integrated professional winter baseball in Cuba.

In Cuba professional baseball was fully integrated (curiously though, amateur Cuban baseball was segregated and only white Cubans could play in amateur teams). As a result of this background, American baseball team owners saw first-hand many great Cuban players of all shades and races play in Cuba, and some of the more enterprising ones began to test the limits and patience of a racist society by introducing some of them to the US public many years before Robinson. But let us first review a little history.

It was then that American students studying in the island taught fellow Cuban students how to play the sport. The game spread quickly, mostly due to the fact that the sons of wealthy Cuban families usually studied in American universities, where baseball was also spreading quite rapidly.

Apparently the first organized baseball game in Cuba took place on December 27, 1874, when the Havana team beat the Matanzas team 51-9 at "El Palmar del Junco" baseball field.

One of the Havana players was named Esteban Bellan, a catcher who was the first Cuban and the first Latin American to play major league baseball. Bellan learned how to play baseball while he was a student at Fordham University from 1863-1868.

During his time at Fordham, Bellan played for the newly created Fordham Rose Hill Baseball Club. This was the team that history tells us played the first ever nine-man team college baseball game in the United States against St. Francis Xavier College on November 3, 1859.

In 1868 Bellan began to play for the Unions of Morrisania, an upstate New York team. A year later he joined the Troy Haymakers for whom he played third base until 1872. In 1871 the Haymakers had joined the National Association, which became the National League in 1876.

The Haymakers later became the New York Giants, now the San Francisco Giants. Later on Bellan was instrumental, both as a player and manager, in establishing professional baseball in Cuba in 1878. He died in 1932.

As early as 1889, the US Major Leagues showed interest in Cuban players, when the legendary John McGraw, who visited Cuba regularly and eventually kept a permanent apartment in Havana, tried to sign a Cuban player named Antonio Maria Garcia (nicknamed "The Englishman" apparently because he was so fair of hair, eyes and skin). Garcia declined, since he was making a higher salary playing in Cuba.

In 1900, a Cuban player named Luis Padron (who as a pitcher had lead the Cuban league in wins and also in hits! Is that incredible or what?) was asked to try out with the Chicago White Sox. However, when doubts as to his racial purity were raised, the White Sox immediately released him and he never played.

A

couple of years later, John McGraw

brought to the US a Cuban player named Luis "Anguilla" Bustamante, who

he called "the perfect short stop." Unfortunately for Bustamante, who

was half black, his timing was off by half a century.

A

couple of years later, John McGraw

brought to the US a Cuban player named Luis "Anguilla" Bustamante, who

he called "the perfect short stop." Unfortunately for Bustamante, who

was half black, his timing was off by half a century.Hearing of Bustamante's prowess, around 1903-4, Clark Griffith, then with the New York Highlanders (later the Yankees), had Bustamante brought up again for a try-out. As soon as Griffith saw Bustamante, according to Angel Torres, author of "The Baseball Bible," Griffith ended the try-out and simply said: "Too chocolate."

Let's now move the clock forward to 1910, when four Cubans debut in the Minor Leagues: Armando Marsans, Rafael Almeida, Alfredo Cabrera and a second chance for Luis Padron.

They play for the New Britain Class B team of the Connecticut League and a year later Marsans and Almeida begin to play for Cincinnati, and that's truly when the issue of race becomes a question in the mind of ignorant racists.

As published in the Cincinnati Tribune on June 23, 1911: The Reds have signed two players from the Connecticut league who have Spanish blood in their veins and are very dark skinned. As soon as the news spread that the Reds were negotiating for the Cubans a protest went up from the fans against introducing Cuban talent into the ranks of the major leagues.

Cuban baseball legend has it that when August Herrmann, the president and owner of the Cincinnati Reds, went to the train station to meet them, he gasped when he saw two young black men come out of the train, and that he even approached them first.

But they were not the Cubans.

The two Cubans had an escort who had brought them to Cincinnati, and he

in turn approached and spoke to a shaky Herrmann, who then met the

Cubans for the first time. Herrmann was pleased and relieved about their

appearance.

The two Cubans had an escort who had brought them to Cincinnati, and he

in turn approached and spoke to a shaky Herrmann, who then met the

Cubans for the first time. Herrmann was pleased and relieved about their

appearance. They were not, as it was incorrectly reported in the next day's paper, "small and swarthy in complexion," [but showed] "practically no effects of the tropical heat and sun." The Reds appeased the alarmed fans by assuring them that both of these players were of pure European blood.

In fact, this was true, as according to Cuban sources and accounts of the times, Marsans was the son of Catalan immigrants to Cuba, and Almeida the son of Portuguese immigrants. This case of first generation Cubans was not that unusual in Cuba during the 1800s (both of them had been born in 1887) and even more after the Spanish-American War. The new nation had just achieved independence from Spain in 1898, and was in the midst of receiving large immigration waves from Europe. The large numbers of immigrants so alarmed native-born Cubans, that afraid that they would be outnumbered by European immigrants, Cuba severely curtailed immigration in the 1930s.

In fact, according to Hugh Thomas, in the first decade of the 1900s alone, nearly 200,000 European immigrants arrived in Cuba. Considering that the 1899 census noted that there were around 1.5 million people in the island, this immigration wave, together with significant immigration by Chinese and Eastern European Jews in the 1920s, had a significant impact on Cuban society and ethnic diversity.

To make matters worse for Marsans and Almeida, it was customary with Cuban and other Latin American players, regardless of race, to play in the US Negro Leagues.

In doing so, players could play year round: summer in the US and winter in Cuba. Both Marsans and Almeida had earlier played in the Negro Leagues.

This probably complicated things for Herrmann, and to further appease the fans, the Reds required that both Cubans bring notarized paperwork from the Cuban authorities, certifying that Marsans and Almeida were indeed white of unmixed blood.

Eventually the Cincinnati press must have been convinced of the racial purity of the Cubans, as a story appeared indicating that the Cubans were "two of the purest bars of Castille soap that ever floated to these shores." It is ironic that neither of the two Cubans was actually of any Castillian ancestry, but Catalan and Portuguese. It is also ironic, and erroneous, that several instances in recent books about Cuban baseball, by American authors, claim that either Marsans or Almeida was half black (and thus the first black person to play in the MLB). However, Cuban sources, such as Gonzalez Echavarria and Angel Torres, as well as the Cuban press of the time, clearly agree that both Marsans and Almeida were "blancos."

The unofficial honor of being the first player of evident African ancestry would fall on the broad shoulders of another Cuban a couple of decades later.

Cubans will also tell you that Marsans had accompanied Almeida as another interpreter, but when the Reds also tested him out, he ended up being the better player of the two and was also signed. Almeida played for the Reds for three years and Marsans ended up playing for many years for Cincinnati, St. Louis and the New York Yankees. In 1924 he also became the first Latin American to manage a professional US team, when he became the manager of the Elmira team.

The uniquely American cultural ignorance about the difference between ethnicity and race continues to this day (especially when dealing with whom we now refer to as "Latinos" or "Hispanics"), as Marsans and Almeida are still often referred to in articles and magazines as "light-skinned Cubans." It is as if the fact that they were born in a Caribbean island had somehow mutated their racial ancestry.

Although the abuse heaped upon them by newspapers, fans and other players eventually diminished, these two Cuban men played a key role in cracking open the race door, which would not open fully for many years later.

In 1912, Miguel Angel Gonzalez made his debut with the Boston Braves, and had a batting average above 300 for the four years that he played (1915-18) for the St. Louis Cardinals. Gonzalez spent 17 years in the majors, and also played for the Reds and Chicago Cubs.

But Gonzalez's true contribution to the story is more profound than his modest .253 career batting average. In 1934, with his playing days over, he was hired as a coach for the St. Louis Cardinals, and in 1938 he was the interim manager for the Cardinals, becoming the first Latin American manager ever in the Major Leagues.

He was fired in 1946 as a result of the famous controversy between MLB and Mexican baseball. Gonzalez is also one of the patriarchs of Cuban baseball, as he managed or controlled the legendary Cuban baseball team Havana Reds from 1914 until the end of professional baseball in Cuba in 1960, when it was terminated by the heavy hand of the Cuban Communist government.

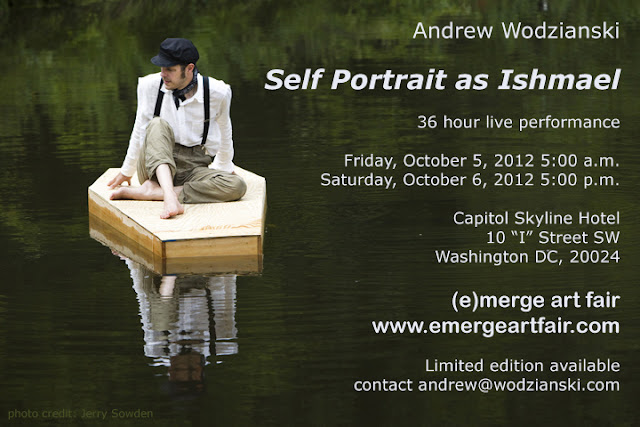

Gonzalez tenure as both a coach in the US Major Leagues (in the photo we see Gonzalez (left) with manager Frankie Frisch and coach Buzzie Wares in the 1930s St. Louis Gas House Gang) as well as the Cuban professional leagues, had a profound impact on the constant flow of both Cuban players up north, and white American players to join integrated Cuban teams during the winter. This unique opportunity in Cuba for black and white American players, together with Cubans and other Latin Americans, to share a baseball diamond, was crucial to the eventual integration of MLB, and Gonzalez must be credited for his very important part in this tortured effort.

But the true patriarch and legendary superman of Cuban baseball, was without a doubt, Adolfo Luque, known in the US as Dolph or Dolf Luque. Much has been written about Luque and his impact on Cuban baseball (none better that Roberto Gonzalez Echavarria's The Pride of Havana).

However, I believe that Luque's contribution to how US owners, fans,

newscasters and players viewed Latin American players, as well as his

outgoing, aggressive personality, and ability to float back and forth

between professional Cuban and American baseball at all levels of

organization, delivered a key ingredient for the eventual breaking of

the race barrier.

But the true patriarch and legendary superman of Cuban baseball, was without a doubt, Adolfo Luque, known in the US as Dolph or Dolf Luque. Much has been written about Luque and his impact on Cuban baseball (none better that Roberto Gonzalez Echavarria's The Pride of Havana).

However, I believe that Luque's contribution to how US owners, fans,

newscasters and players viewed Latin American players, as well as his

outgoing, aggressive personality, and ability to float back and forth

between professional Cuban and American baseball at all levels of

organization, delivered a key ingredient for the eventual breaking of

the race barrier.Luque was the first true Latin American star of the Major Leagues. He won nearly 200 games, played in nine World Series, and in 1918 had an astonishing 27 and 8 record with a 1.93 ERA while playing with the Cincinnati Reds.

He was also a man who did not take insults from anyone, and according to Gonzalez Echavarria, he was a "snarling, vulgar, cursing, aggressive pug, who, although small at five-seven, was always ready to fight."

These characteristics served Luque well in the racist environment of the early 20th century MLB. Although he was very fair and blue-eyed, and no one could distinguish him from the other white players until he opened his mouth, Luque was nonetheless the butt of many racial insults, to which he usually responded with brutal beanballs.

Once, while

pitching for Cincinnati, Luque heard insults coming from the Giants'

dugout. The fiery Cuban charged the dugout and punched Casey Stengel in the mouth (Stengel later claimed it wasn't him who had called Luque a "Cuban N-word," but it was the man seated next to him, Bill Cunningham).

The police sent Luque back to his bench, but his Cincinnati teammates

took over the fighting to restore Luque's honor, and a near riot began.

In the chaos of the fighting, Luque grabbed a bat and headed back to the

Giants dugout.

Once, while

pitching for Cincinnati, Luque heard insults coming from the Giants'

dugout. The fiery Cuban charged the dugout and punched Casey Stengel in the mouth (Stengel later claimed it wasn't him who had called Luque a "Cuban N-word," but it was the man seated next to him, Bill Cunningham).

The police sent Luque back to his bench, but his Cincinnati teammates

took over the fighting to restore Luque's honor, and a near riot began.

In the chaos of the fighting, Luque grabbed a bat and headed back to the

Giants dugout.Order was finally restored and both Luque and Stengel were ejected. It was not the first time that the aggressive Luque had taken matters into his own hands, for earlier in his career he had also fired a ball into his own dugout and chased one of his own teammates with an ice pick.

Luque died in 1957, after playing in the Majors from 1914-1935. After his playing career ended, he returned and began coaching in 1941 in the US Major Leagues and also managed several teams in the Cuban League (he even pitched in a game in 1946, when he was pushing 55) as well as many other teams in Latin America.

Adolfo Luque's overall impact upon the world of professional baseball certainly merits his inclusion in the Baseball Hall of Fame, where many lesser players of his era are included. As his New York Times obituary

testifies to, Luque was a respected coach in the Major Leagues, and

like Gonzalez, had a significant part in helping to establish Latin

American players as part of the national game.

Adolfo Luque's overall impact upon the world of professional baseball certainly merits his inclusion in the Baseball Hall of Fame, where many lesser players of his era are included. As his New York Times obituary

testifies to, Luque was a respected coach in the Major Leagues, and

like Gonzalez, had a significant part in helping to establish Latin

American players as part of the national game.Because of his temper, Luque also commanded a respect, sometimes out of fear, that also played a key part in the acceptance of Latin American players, and helped immeasurably in paving the road for Robinson and all the others who followed in his steps. As Hemingway wrote in The Old Man and the Sea: "Who is the greatest manager, really, Luque or Mike Gonzalez? -- I think they are equal."

Between 1911 and 1929, seventeen Cuban-born Caucasian players played in the Major Leagues and many more, both black and white, in the Negro Leagues. Somehow, along the line, and probably helped by the full acceptance by MLB of players and coaches like Gonzalez and Luque, and clearly assisted by the exposure of American owners, white players and managers to Cuban baseball players, the pedigree requirement for obvious "whiteness" was discarded. As a result, in 1935, a Cuban of clearly defined African features makes his debut with the Washington Senators.

There exists a fairy tale perception in the United

States of a Cuban society that is a fully integrated, equal society

where race doesn't matter, and everyone lives in a happy melting pot

where the races mix and blend and racism is not a problem. Nothing could

be further from the truth, even today (especially with the revival of tourism), and while many advances have been made for racial equality

in Cuba, this perception diminishes the suffering and pain that

Afro-Cubans, like African-Americans, have had to endure for centuries.

There exists a fairy tale perception in the United

States of a Cuban society that is a fully integrated, equal society

where race doesn't matter, and everyone lives in a happy melting pot

where the races mix and blend and racism is not a problem. Nothing could

be further from the truth, even today (especially with the revival of tourism), and while many advances have been made for racial equality

in Cuba, this perception diminishes the suffering and pain that

Afro-Cubans, like African-Americans, have had to endure for centuries.Cuba even had a race war in 1912, in which thousands of Afro-Cuban militants, demanding equal rights, were massacred in a matter of weeks by the Cuban Army. This genocide was the most dramatic example of how white Cuban rulers responded to demands for racial equality at the same time that Marsans and Almeida were playing in the Major Leagues.

As Roberto Gonzalez Echavarria eloquently discusses in his book The Pride of Havana, Cuban baseball was curiously integrated at the professional level while being racially segregated at the amateur level. The image at the top left says it all: It is the 1914 amateur team of the Central Soledad, a sugar mill plant near Guantanamo. The vast majority of Central Soledad's people were black Cubans, many of Jamaican and Haitian ancestry, and yet not one black man is represented in the team.

The Cuban baseball racial paradox is perhaps inexplicable to Americans, but made perfect sense in the racist Cuban society of the 20th century, which even allowed a President of mixed blood (the tyrant Fulgencio Batista) to take over the government in 1933, and yet refused him membership into the Havana Yacht Club, which only allowed white members.

But in professional Cuban baseball, black and white Cuban players, together with black and white professional American players and newscasters, as well as visiting US Major League teams, played in curious indifference to the racial division of baseball in the United States, and clearly showed Americans that black players - both Cuban and American - could play on an equal level to the MLB visitors.

Roberto Estalella was a handsome, powerful man, and his muscular appearance earned him the nickname "Tarzan" in the Washington press. He was also a man of evident African features, who in Cuba would not have been called black, but perhaps mulatto, or in the Cuban slang "jabao," which is the equivalent of the term "high yellow" used by African Americans to describe a light skinned person with some African ancestry, although in Cuba, "jabao" is not a pejorative or derogatory term.

Estalella's professional US career started with Albany in 1934 and then he played for nine seasons with the Washington Senators and the Philadelphia A's and also for other Minor League teams in the Deep South (he played for Charlotte and he also led the Piedmont League in batting two years in a row in 1937 and 1938). He would have played many more years, but he was one of the players fined by MLB for his part in the Mexican League fiasco of the 1940s.

What tribulations Estalella must have endured! He was no blue-eyed, pale skinned

Luque, able to blend in visually, and certainly in the Deep South, no

one was fooled by the owners' claim that Estalella was not black but

Cuban.

What tribulations Estalella must have endured! He was no blue-eyed, pale skinned

Luque, able to blend in visually, and certainly in the Deep South, no

one was fooled by the owners' claim that Estalella was not black but

Cuban.But the spectacular deception worked, at least on paper, and this talented athlete thus became the first man of recognizable African ancestry to play Major League Baseball in the US.

Were there players before Estalella who had some African blood? Probably, as race mixing was not a unique Cuban phenomenon, and there are many instances of "white" American players with African features being passed as "Indian" and being abused by fans and other players (in fact, recent DNA studies show that as many as 50 million white Americans have a black ancestor in their family tree).

Babe Ruth was perhaps the most famous example of this point. "Ruth was racially insulted so often that many people assumed that he was indeed partly black and that at some point in time he, or an immediate ancestor, had managed to cross the color line," wrote Ruth biographer Robert W. Creamer. "Even players in the Negro baseball leagues that flourished then believed this and generally wished the Babe, whom they considered a secret brother, well in his conquest of white baseball."

While there's no evidence that Ruth had any black ancestors, the racist American belief that any possibility of African blood immediately makes the person "black" was disregarded in the case of Estalella, and later in the case of Tomas de la Cruz, another Cuban player of obvious African ancestry who played for

Cincinnati in 1944, as well as a Cuban of Chinese ancestry, Manuel

"Chino" Hidalgo, who was signed by the Senators and played in the Minor

Leagues, but never broke into the majors. Hidalgo was probably the first

man of Asian ancestry to play in organized professional baseball in the

US.

Cincinnati in 1944, as well as a Cuban of Chinese ancestry, Manuel

"Chino" Hidalgo, who was signed by the Senators and played in the Minor

Leagues, but never broke into the majors. Hidalgo was probably the first

man of Asian ancestry to play in organized professional baseball in the

US.Another Cuban baseball legend is the story of Branch Rickey and black Cuban player, Silvio Garcia.

If

we are to believe many Cuban stories of the times, Branch Rickey

started to seriously consider that the best strategy to break the color

barrier would be by bringing a black Cuban player to the major leagues.

His initial choice was a very good Cuban shortstop, Silvio García. According to Edel Casas,

the noted Cuban baseball historian, Rickey met with García in Havana in

1945 to explore the possibility of bringing Garcia to the Dodgers.

If

we are to believe many Cuban stories of the times, Branch Rickey

started to seriously consider that the best strategy to break the color

barrier would be by bringing a black Cuban player to the major leagues.

His initial choice was a very good Cuban shortstop, Silvio García. According to Edel Casas,

the noted Cuban baseball historian, Rickey met with García in Havana in

1945 to explore the possibility of bringing Garcia to the Dodgers.As he would later do with Robinson, Rickey interviewed García and asked him: "What would you do if a white American slapped your face?" García's response was succint and sincere. "I kill him," he answered. Needless to say, García was never a choice after that.

In

1947, after Robinson finally broke the obvious racial barrier for

African-Americans, many black Cubans followed in his steps, in many

cases becoming the first black players in many MLB teams. None of these

was greater than Orestes Miñoso,

called "Minnie" in the United States. On April 19, 1949 Miñoso made his

debut with the Cleveland Indians, and became the first black Cuban and

Afro Latin American to play major league baseball. He collected 1,963

hits in his career and became the second major leaguer to play in five

different decades.

In

1947, after Robinson finally broke the obvious racial barrier for

African-Americans, many black Cubans followed in his steps, in many

cases becoming the first black players in many MLB teams. None of these

was greater than Orestes Miñoso,

called "Minnie" in the United States. On April 19, 1949 Miñoso made his

debut with the Cleveland Indians, and became the first black Cuban and

Afro Latin American to play major league baseball. He collected 1,963

hits in his career and became the second major leaguer to play in five

different decades.However, like their American colleagues, many other earlier great black Cubans, such as the legendary Martin Dihigo, now in the Hall of Fame, never had a chance to play in the Majors.

It is thanks to the forgotten accomplishments of white Cuban players such as Gonzalez and Luque, and the hidden sacrifices of Cubans of color like Estalella and de la Cruz, and to the final smashing of the color barrier, accomplishments and sacrifices by Robinson, that many of today's stars of color from Latin America, Asia and the United States owe their success.

Great black Latin American players of all nationalities, such as "El Duque" Hernandez, Tony Oliva, the great Roberto Clemente and the record-breaking king of the long ball, Sammy Sosa continued to break new barriers and records, even in the 21st century, but they stood on the shoulders of those brave men who played in a brutal field where race was used as a weapon to diminish and destroy.

And perhaps there is no link more brilliant to this past than Roberto Estalella's grandson, Bobby, also a great Major Leaguer, who carried the great baseball tradition

of this unheralded hero of the past.

And perhaps there is no link more brilliant to this past than Roberto Estalella's grandson, Bobby, also a great Major Leaguer, who carried the great baseball tradition

of this unheralded hero of the past.This is a work in progress which ultimately will produce a book on this subject as well as a traveling photography exhibition. Please email me if you have any questions, corrections, additions, updates, images, etc.