Bruce McKaig on CHAW's 4th Annual Photography Exhibition

By Bruce McKaig

Why have an exhibition of contemporary photography? Why send out a call-for-entries, review submissions, select some to hang on the walls of a gallery? Why have an opening reception, attended mostly by the participating artists and their social circles, then return most of the work to the artists a few weeks later? How did such a ritual begin and why does it persist?

Exhibitions at art galleries are a fairly modern practice. As submitted by Ethan Robey in The Utility of Art: Mechanic’s Institute Fairs in New York City 1828-1876, they are an offshoot of state or national fairs, where booths are set up and visitors can look at mechanical gadgets, scientific discoveries, jellies, pies, and well-bred livestock. By the late 19th century, some artists were hosting public receptions in their studios.

Eventually, some entrepreneurs – like Steiglitz and his Gallery 291 – decided to propose a year-round place where art and public could meet. As I looked at submissions for CHAW’s fourth annual photography exhibition, and as I gear up for my next solo exhibit at the Orlando Museum of Art, I find myself asking: Why not open year-round places for public and livestock to meet? Who doesn’t love beautiful sheep, especially a young one? Would a galerie des moutons be more preposterous than an art gallery?

Photography became public property in 1839 when Daguerre read his process out loud to the French senate. Photography was democratized in the 1880s when Thomas Edison invented 35mm film and George Eastman invented the word Kodak. In the mid-to-late 19th century, both the making and the viewing of photographs were not so much a daily bombardment as they were occasions. In most cases, if several people were to look at a photograph, they would usually be in the same room at the same time.

Clearly, that has changed.

According to The Camera and Imaging Products Association (CIPA), the number of digital cameras shipped in 2008 was 119,757,000, not including cell phones. As of October 2009, there were four billion images on Flickr. With over 300,000 images uploaded to Facebook every second, there are over 850 million images added every month. Last summer, I photographed a wedding and had to edit out numerous images that were overexposed because of how many other flashes kept firing. It seemed like most guests were also photographers.

On a recent field trip to the US Botanical Gardens, the number of people taking pictures was truly phenomenal. From cell phones to cumbersome SLRs with hefty attached flash units, people were lining up to photograph or be photographed in front of various floral arrangements amidst the holiday decor. Such colossal production rates beg the question, how much time do people spend looking at photographs? Has the priority, the principle activity, become making, not viewing?

The persistence of exhibitions and the excitement over the Internet coexist because one confronts confusion with a semblance of order; the other confronts the semblance of order with confusion. The gallery’s elitist approach strives to select and organize works in a momentary setting, as much an event or performance as a body of work, all in an effort to provide ground for discovery, debate, and direction.

The Internet’s democratic approach strives to neither select nor organize images, and the 24/7 open call-for-entries results in a bubble that can never burst because it has no dates, deadlines, or locale. The perception that the Internet is everywhere and always open implies both a trust in its availability and a lack of urgency, or even preciousness, when it comes to discovery, debate, or direction.

I suggest that people go to exhibitions because sometimes there is a precious urgency to discovery, debate, and direction.

The Fourth Annual Photography Exhibition at Capital Hill Arts Workshop is, once again, a sampling, an across-the-board look at diverse ways artists chose to approach the medium of photography, produce a piece, and connect with a viewer. By no means exhaustive, the diversity of the works conjures thoughts on defining what is an artist and what is a successful photograph. The diversity, however, does not succeed in masking the various themes that appear across the works when compared and contrasted.

Several of the images are formal studies, exploring shape and color. Red Deck, by Mark Walter Braswell, is a color image of the side of a building. Not an architectural study, with a confusing rather than informative perspective, the geometry and color are all that is left, is needed, to contemplate. Sue Weisenburger’s works are also formal studies. Foundation is more rigid, V&A in December is more organic, but both brush up against the narrative with their poetic use of geometry. In Vickie Fruehauf’s black and white scenes of water, the formal qualities have been wedded to an almost spiritual presence, in her words, “the silent observers within the natural world.” Judy Searles’ images are close-up looks at elemental materials. The materials, initially man-made, have been shaped and colored by the battering of weather and time. The temporal aspect to her work is explored in different ways by several other artists in the show.

Time as an element in photography is explored in several artists’ works, through the blurry stretching of time, or the juxtaposition of images side-by-side or sequentially in a slideshow format. Tom Pullin layers the fourth dimension of time into Fussa-Tokyo33107 thanks to a slow exposure. Similarly, Jim Blackie’s Down depicts an isolated traveler descending a quivering escalator. In the Motion Studies portfolio by Mark Issac, temporality is explored through, in Issac’s words, “the manner in which solid objects break apart and dematerialize.” Patricia Goslee and Siobhan Hanna both work with multiple images and the juxtaposition of different angles or objects has an element of time travel. In the back-and-forth observation for a viewer, the passage of time becomes a part of the experience. Leland Bryant also uses multiple images, but strings them out in a slide show. In this format, the images move by at the author’s chosen pace, not the viewers, and they run from first to last per author’s selection. Goslee, Hanna and Leland all use somewhat cumbersome titles or text that the viewer is left to appreciate or ignore.

Photo documentary works are also part of the exhibition. Gabriela Bulisova exhibits three images of anonymous Iraqi refugees. Heads cut off – by the picture frame – or eyes banded – by a wooden railing – or the human body replaced by its shadow, these images speak both of the individual and the collective. Kristoffer Tripplaar exhibits five images from Galveston Texas in the wake of a natural disaster. There are no people in Tripplaar’s images, just man-made structures with signs of nature’s rage. The absence of people succeeds in broadening the images’ story to a more universal struggle between urban humanity and nature. Another image in the show that uses absence to create atmosphere is Christopher Schwartz’s Off Duty, a shot of a deserted lifeguard station. Without people or activity, the strong colors come across bleak and doll-like. People are full-face present in Michael Stargill’s documentary sports images in a somewhat comical, somewhat iconic mixture of reportage and theater.

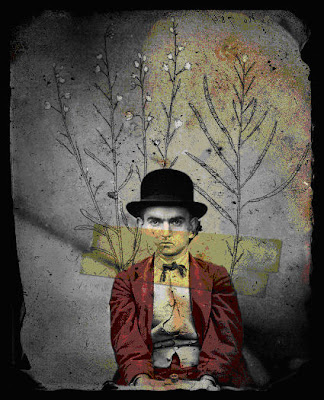

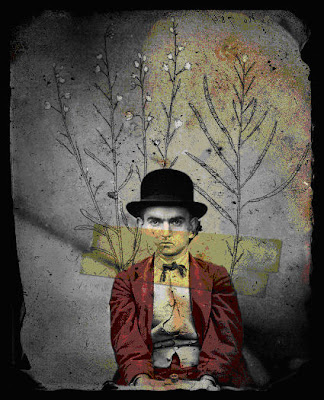

Photo by Jared RaglandSeveral other artists in this exhibition turn directly to iconic elements and theatrical approaches. Jared Ragland’s socio-political commentary uses iconic items to construct blunt social commentaries. Ragland’s artist statement says, “While not always adhering to the traditional structure of narrative I seek nonetheless to open relationships between fragments of content and combine images to form loose associations and representations of the subconscious.” Whereas Raglan constructs his choreography with photomontage, Carolina Mayorga goes directly to theatrics in her exploration of religious ritual and rhetoric. Mayorga’s artwork addresses issues of social and political content and are produced as a mixture of drawings, sculptures, videos, or performances.

This exhibition fails to answer my questions about photography but succeeds in furthering the discovery and debate. I still don’t know how much time people spend looking at photographs. I still don’t know if a gallery of sheep would be more or less preposterous than a gallery of art.

What: CHAW”S 4th Annual Photography Exhibition

When: Jan 9th – Feb 4th 2010, opening reception Sat Jan 9th 5-7pm

Where: Capitol Hill Arts Workshop 545 7th Street SE WDC 20003

202 547 6839

www.chaw.org